Grieving Glaciers Past: The Artists of the Terminus Project

Thirty-eight artists have come together to document the disappearing glaciers in Olympic National Park.

May 31, 2023

This story has been edited post-publication for clarity and accuracy.

Story by Elly McFarland

Bill Baccus, physical science technician at Olympic National Park, remembers hiking the Bailey Range Traverse in the summer of 1989, where he came face to face with the Ferry Glacier. He moved through the glacial terrain quickly with his group as the low clouds coated them with snow and rain. He took a few pictures of the blue cracked ice and continued on his way.

Years later, in 2006 he was in the midst of a research project that included monitoring randomly selected alpine lakes. Baccus found himself next to Iceberg Lake, an incredible blue alpine lake surrounded by sparse vegetation. At the time he did not realize he was standing in nearly the same spot he was 17 years prior.

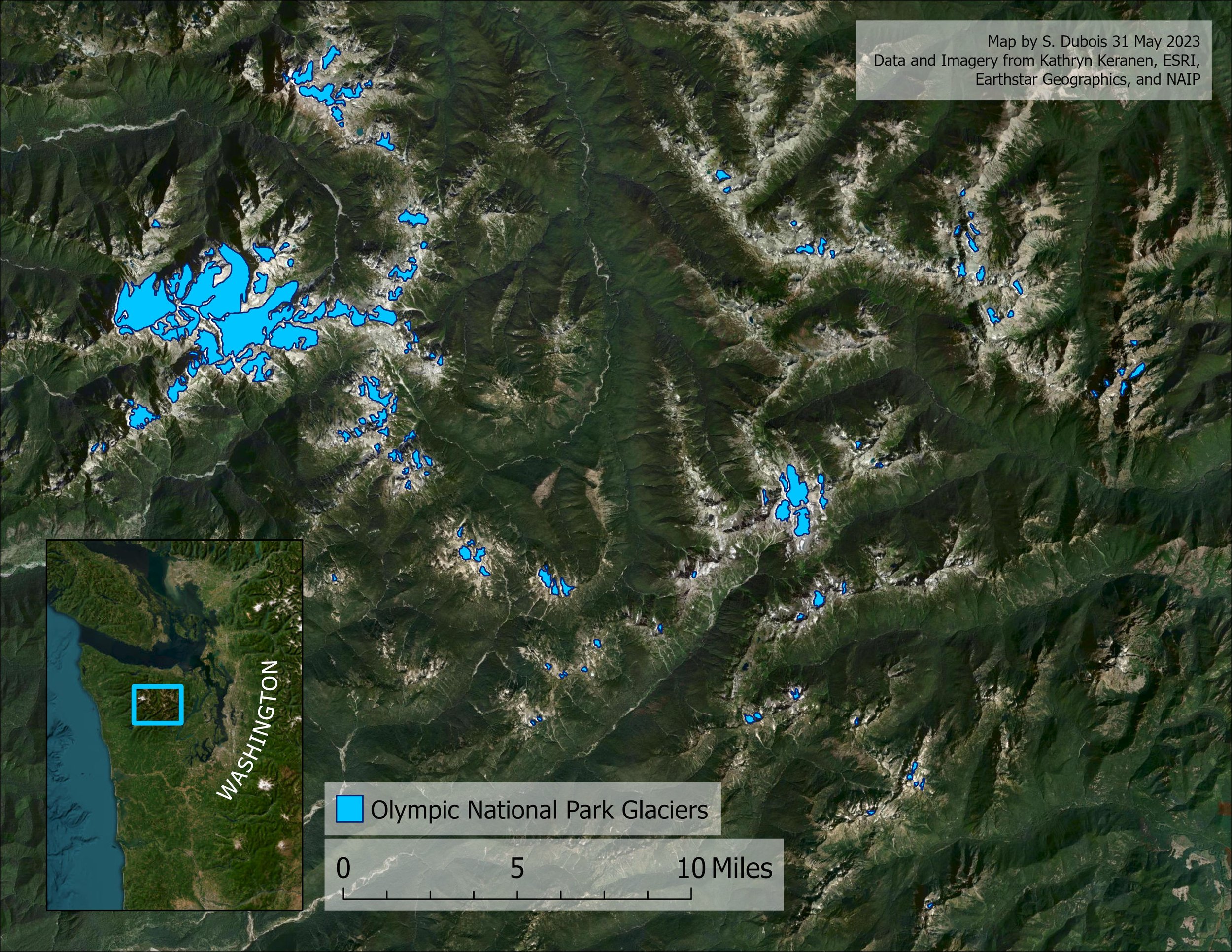

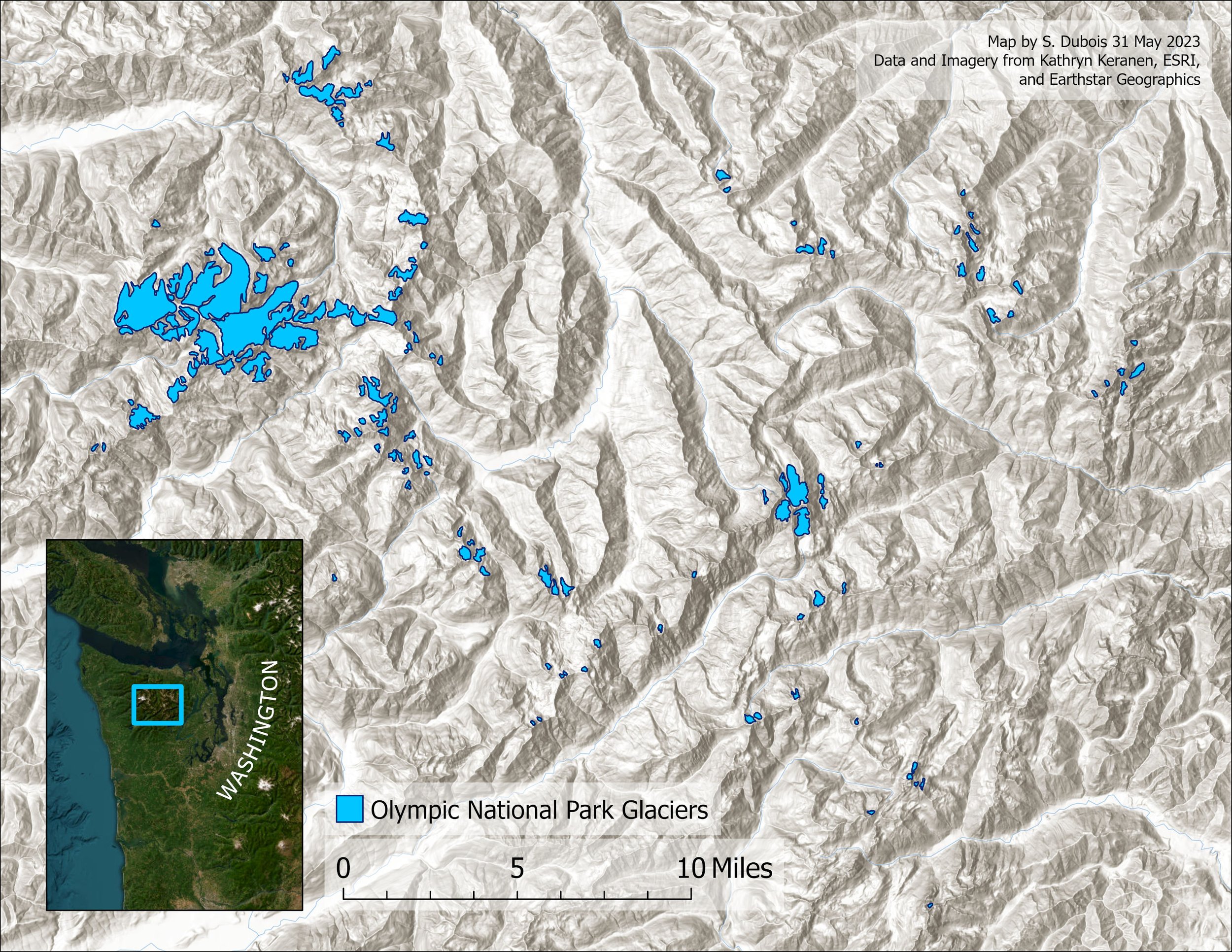

Glaciers are a cornerstone of Olympic National Park but are rapidly disappearing from the landscape – 82 glaciers have disappeared completely since 1980. The Terminus project offers a new perspective to the conversation surrounding how climate change is rapidly manipulating landscapes. Drawing inspiration from data, archival photos or their own experiences, artists use a variety of mediums to depict the glaciers past, present and future.

A few years ago, interpretive rangers at Olympic National Park were brainstorming project ideas when visual information specialist Eliza Goode said, “What if we assigned an artist to every glacier in the park?”

About a year later a colleague surprised Goode with the news: Olympic National Park received funding from Washington's National Park Fund for what would become the Terminus Project.

“Data doesn’t really tell a story other than charts changing,” said featured artist Amory Abbott. “We need art to supplement [data] or to walk in hand with data in order to tap into a lived experience.”

Glaciologists define terminus as the end of a glacier at any given point in time. The Terminus project’s website defines the project as an artistic elegy, a love poem to a changing planet. The website is continuously updating as artists finish their work. The content is available through the Olympic National Park website, and will be exhibited at the Port Angeles Fine Arts Center in the summer of 2023.

“It's pretty likely that we are the last generation that could know these glaciers firsthand,” Goode said. “You will probably outlive them yourself.”

During Baccus’s first visit to Ferry Glacier, it was 0.07 square miles in size, making it one of the 50 largest glaciers in the Olympic Mountains. Aerial photographs taken in 2009 parallel Baccus’ account. What remained of the glacier was covered by a rockfall, making it hard to determine if there was any ice remaining at all.

Every year the Olympic Mountains are losing an average of 0.18 square miles of glaciated surface area. The Olympic range is particularly vulnerable to warming as this area typically experiences mild winters with air temperatures close to freezing. Climate models suggest that nearly all the glaciers in Olympic National Park will disappear by 2070.

The glaciers are a vital resource for the people, fish and forests in the valleys and lowlands. Continued loss of glaciers will directly impact aquatic ecosystems, causing higher stream temperatures and lower volume in the Hoh and Elwha Rivers and their tributaries.

The Lillian Glacier, a watercolor painting by Claire Giordano. // Courtesy of Claire Giordano

Claire Giordano, a featured artist who documented the disappearance of the Lillian Glacier, is motivated by environmental advocacy. She hopes that this project will inspire action to better care for these ecosystems.

“I think an emotional and personal connection to a place, whether it's something they see through my painting or a place they know and love from their personal experience, that is the foundation for environmental stewardship and environmental action,” Giordano said.

Featured charcoal artist Amory Abbott recognizes the emotional toll of the current climate crisis and wants to explore the process of grieving a glacier in his work.

“Feeling a loss of us, or a glacier, or a climate is something worth spending time with and really sitting with,” Abbott said. “Not just trying to look for the hope, or just trying to get back to feeling good again, it's a process we really can't afford to skip at this point.”

Painting the Black Glacier

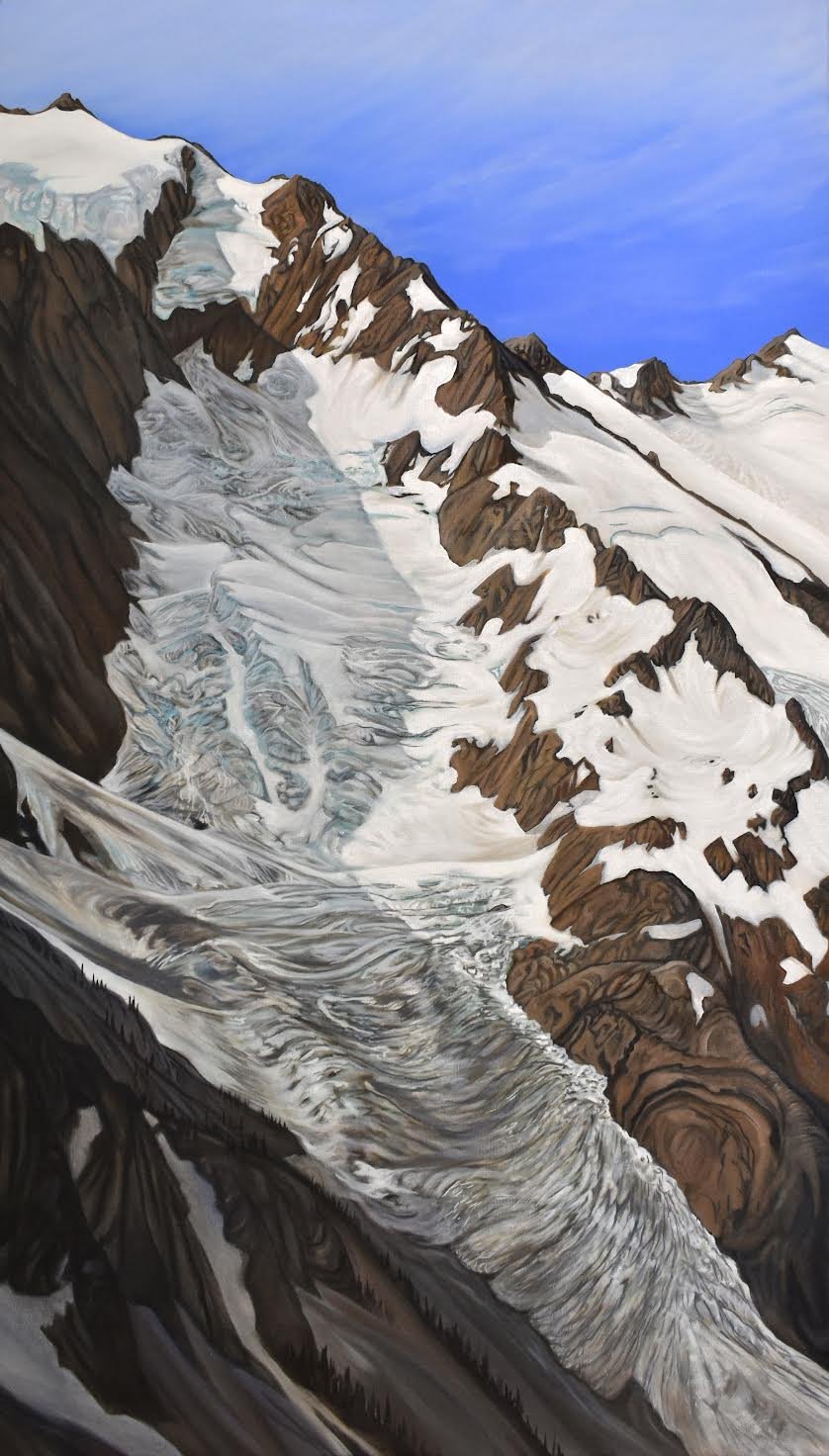

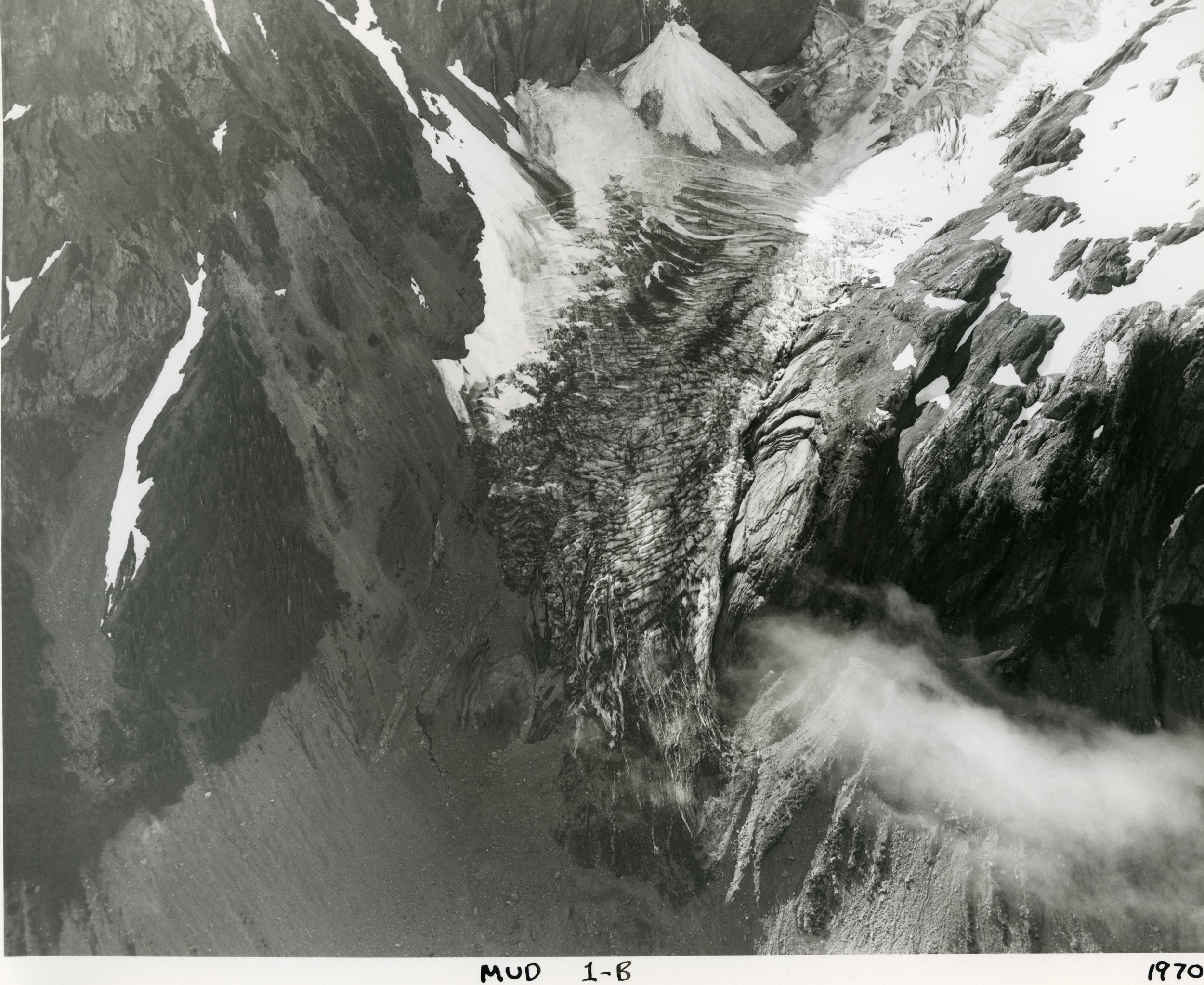

Klara Maisch, featured artist, worked from a small black and white photo of the Black Glacier to create a large oil painting.

“You can only blow that image up so far before you start to lose the integrity of the visual,” said Maisch. “I think that’s why a painting can kind of bring us there, or transport us or translate something that maybe a photograph can’t.”

Rising to the challenge, Maisch filled in parts of the photo that were poor quality or missing entirely. She used her imagination and knowledge of how glaciers move and fill landscapes while she paints. Based in Alaska, Maisch has observed changes in the glacial landscape of her own backyard.

“It's been very interesting thinking back in time, because I think that's what allows us to think forward in time,” Maisch said.

Maisch is fascinated by the science behind the “geophysical happenings” she observes. She thinks art can make scientific literature more accessible to a broader audience.

“I think it might not reach everybody, but it reaches a new audience beyond those who might be exposed to the science or to this place,” said Maisch.

The Sounds of the Eel Glacier

Thomas Peters, a composer working on the Terminus Project, uses music to transport listeners to the Eel Glacier through a bass line. Peters ties climate data to the elements of the music. His piece portrays the increasing global temperature, as the central chord of the song rises faster and faster.

Peters hopes that when park visitors stumble upon the Terminus website through the Olympic National Park website it will leave a lasting impression.

“I think the biggest impact is going to be somebody discovering that, visiting the park and then being aware of the fact that there are glaciers and that they're disappearing,” Peters said.

Drawing Mount Steel Glacier’s Story

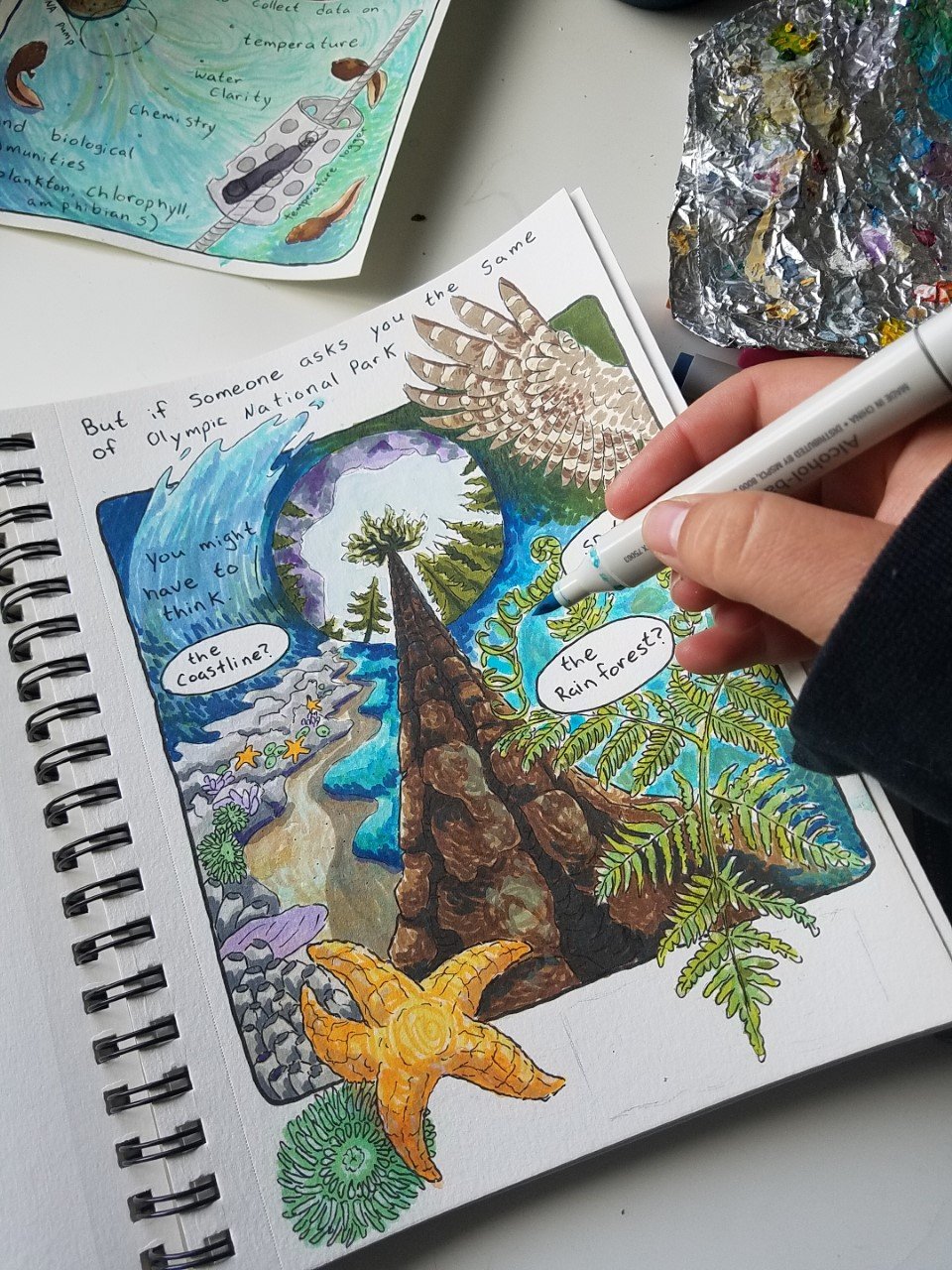

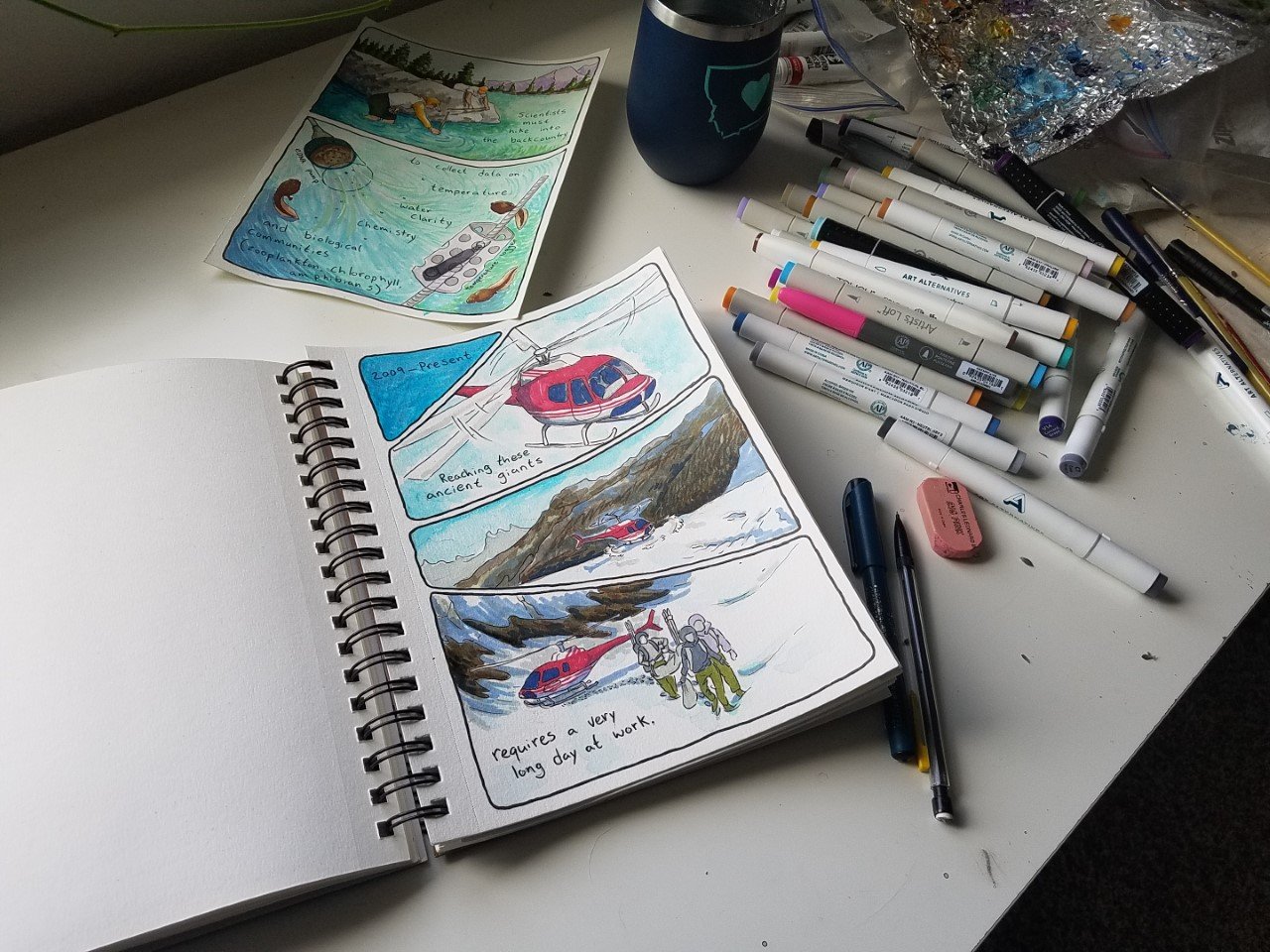

Madi Bacon is writing and illustrating a comic about the Mount Steel Glacier while incorporating stories about the work of researchers monitoring glaciers.

“My comic is about Mount Steel, but I feel like it is more about documenting the effort that's been put into researching the glaciers,” Bacon said. “In a sense it is so people can remember Mount Steel, but it's also to document for people, this is the work that has been done for them.”

The Mount Steel Glacier is small. Bacon said that it has more characteristics of a permanent snowfield than a glacier. For this reason, the Mount Steel Glacier doesn’t have time and resources devoted to studying it.

“While we're looking away, will the Mount Steel glacier blip out of existence?” Bacon said.

Their comic urges the reader to think about the importance of understanding how these glaciers are changing, the impact of the changes and why we care.

“Is it important that we know the exact day that this glacier disappears? On the other hand, it's sad to think about it disappearing and us not noticing right away,” Bacon said. “There’s an emotional heaviness of not studying this one, but it is going to disappear. How does that make us feel?”

Preserving the Memory of Glaciers

As the artists continue to compile their work on the Terminus website, the project will eventually come to an end. The artwork created for the Terminus project will be accessible long after the glaciers are gone.

“Recognizing that we're not alone, that we all share these fears, or that we all care for things that are worth saving is how we can come together to find solutions or to act on solutions that already might exist,” Goode said.

The mission of the National Park Service is to preserve and protect the plants, animals and land within a politically created boundary. The Terminus project is a new approach to preserving the memory of these unique landscapes of the Olympic National Park.

“At least we recognized that they were important,” said Abbott. “At least we made some artwork about how we felt about it and documented this time and what we made of it all.”

Bacon compares looking back on the Terminus project to looking back at pictures of old friends you’re not in contact with or have passed.

“You're glad that you have the photograph, you're glad you have the memory, but it also is kind of sad to know that they're gone,” Bacon said.

Elly McFarland is an environmental science student at Western’s College of the Environment.