Losing Lampreys

An ancient fish is on the verge of disappearing from Washington waters

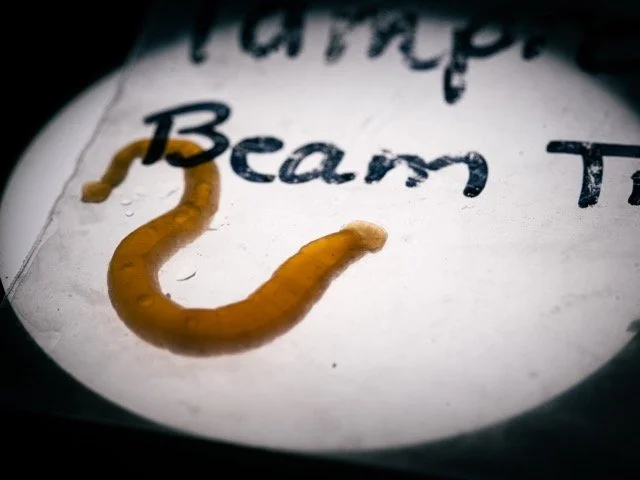

Lamprey under a microscope for observation.

Story by Stephanie Larsen // Photos by Gareth Miller

June 26, 2025

In the Columbia River, the lampreys propel themselves through the water, their dark eel-like bodies undulating as they swim. They suction onto the rocks to rest, using their disc-shaped mouth of spiraling hooked teeth to hold on. These fish are prehistoric, around for over 350 million years and pre-date the dinosaurs. Despite being around for so long, their populations in the Pacific Northwest are starting to decline at an alarming rate.

Lamprey often go unnoticed, but these slippery fish play a crucial role in the ecosystem. They are important to many Indigenous nations, especially to the Nez Perce, Umatilla, Warm Springs and Yakama tribes that live within the Columbia River Basin. Physical barriers, such as dams and contaminated waterways, have led to population decline.

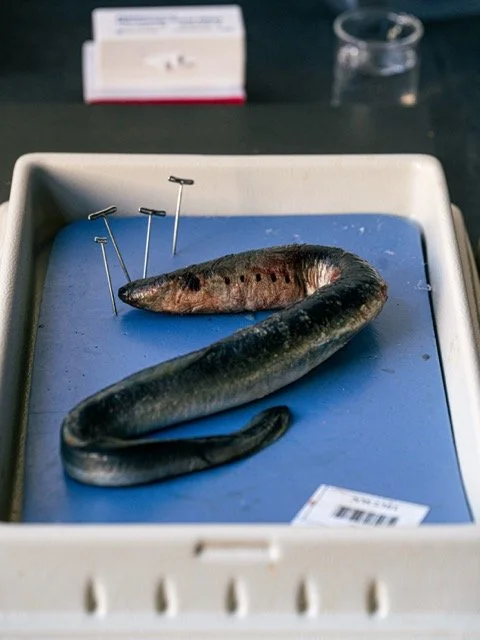

Lamprey observation in progress in a WWU lab.

Luckily, there is action being taken to help them rebound.

Niamh Balaji, a student at Western Washington University, has been researching lamprey for the past four years. Most of her research has been with arctic lamprey in Canada and Alaska, but she first started her work with Pacific lamprey when she was in college in Walla Walla before transferring to Western. She has helped with conservation as a lab technician in the Columbia River Basin and did artificial propagation to restore the population.

Balaji stresses that lamprey are beneficial for river ecosystems. While salmon often get the spotlight, lamprey play just as large of a role. Both species also provide a food source for the Columbia River Basin tribes.

Despite looking so different, lamprey and salmon go through similar stages of life.

“Just like salmon, they come back to the river and they spawn and they die, and then all of the nutrients that they’re holding onto get released back into the river,” Balaji said.

Also like salmon, lamprey face many of the same threats, the biggest being dams built along the rivers that prevent lamprey and other fish from getting upstream. There are several hydroelectric dams in the Columbia River alone, and each pose a hindrance to lamprey returning to their spawning grounds. In each of the dams, fish ladders have been installed that have helped salmon get past the dams, but these fish ladders do not give passage for lamprey.

“The lampreys’ biology, their morphology, is just different,” Balaji said. “It is very difficult for them to use those fish ladders.”

There is a lot of work going on to get lamprey across the dams. One of the ways that researchers have done this is by trapping lamprey and transporting them over the dams so that they can spawn.

“We suspect that we lose 50% of the population going over each dam. It’s not that they die; it’s that they’re not making it over the dam,” said Dave’y Lumley, a lamprey biologist with Yakama Nation Fisheries.

To mitigate this problem, researchers transport the lampreys in trucks as far as Portland and the Tri-Cities, where they’re released past the dams.

Aside from transporting lampreys, slides have been installed on dams that act as a passageway for them to cross.

Laurie Porter, the lamprey project lead for the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission, has been involved in developing these lamprey passage systems.

“[The slides are] how we collect some of our lampreys. They go up the [lamprey passage system] and they have a rest box. In that rest box, we can set it either closed so that we can trap, or we set it open so they can keep going. It makes things so much easier,” Porter said.

The commission has been developing new ideas other than the slides to ensure passage for lampreys across the dams. They’ve developed wetted walls, which are similar to the slides and allow the lamprey to climb up with their mouths while water flows past them.

Another idea for lamprey passage will be implemented at the Bonneville Dam later this year.

And it’s a floating trap, placed at the tail end of the dam.

These short-term solutions have allowed lamprey to get across, but they still do not address the root of the issue —the dams are still blocking their passage upstream.

Removing dams entirely would likely help the lamprey population by removing the barrier, but dam removal is a complex process. It is extremely expensive, takes a long time and needs political support to happen. These short-term solutions are easier as they are not as extensive as removing an entire dam.

Another major issue that lamprey are facing right now is pollution and contamination in their waterways. Ralph Lampman, a lamprey research biologist with Yakama Nation Fisheries, has been working with lamprey for 13 years in the Yakima River Basin.

“We’re getting a better idea of what [pollutants are] in them, but how that impacts them, we don’t fully understand,” Lampman said.

Mercury and phencyclidine were the most problematic contaminants found. This triggered a consumption advisory in lamprey, meaning that they were no longer safe to eat.

Lamprey are significant to Indigenous peoples in many different ways. According to U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services, Pacific lamprey are considered a first food, having ties with tribal culture, and are also used at ceremonial tables and for medicine. Lumley mentioned that lamprey have more nutritional value and caloric density compared to salmon.

“Because populations are so limited, there’s really only one location where tribal members can harvest lamprey in large quantities, and that’s at Willamette Falls,” Alexa Maine, a lamprey biologist through the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, said. “The dream is that someday we will have a tribal harvest on tribal lands.”

Whether swimming with the dinosaurs or taking a taxi, lampreys are persistent and resilient. However, dams and pollutants threaten to end their legacy. They may not be the most attractive, but these fish fill a cultural and ecological niche unlike any other.

“When elders talk about [lamprey], they talk about it as if they are missing a family member and one that they really miss,” Lampman said.

Lamprey researcher writing down observations in the lab.